Found in Translation, Lost in its Prizes: The Trouble with Translated Literature Awards

It’s no secret that the translated novel is a rather odd duck in the British literary pond. While in other countries literary translations are broadly published and read, the Anglo-American world seems stubborn in its preference for homegrown literature. Currently attempts are being made to boost the popularity of foreign works through the introduction of new literary awards. But to what extent can literary prizes really help foreign authors to get a firm footing in the English literary market?

The phenomenal global success of The Vegetarian by Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith, exemplifies how prizes such as the Man Booker International can propel a foreign novel into worldwide readership. While in the nine years of its existence prior to winning that prize in 2016 The Vegetarian sold about 20,000 copies, after the prize, sales skyrocketed to over 462,000 copies worldwide. In consequence, not only did Kang’s career reach new heights, but Korean literature was also put on the map.

Literary prizes do more than just drawing attention to a translation: they can raise the translator’s profile as well. Since 2016, the annual Man Booker International has split the £50,000 prize money evenly between author and translator, recognising the craftsmanship that goes into translated works. Too often, as we have argued in our “Remember the Translator” blog post, the translator’s efforts are forgotten, so recognition from renowned awards like the Man Booker International is a helpful first step in bringing about much-needed change in the industry.

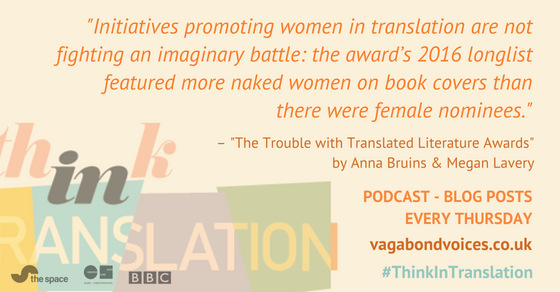

Translators are not the only ones occupying the margins of the world of translated literature: a study conducted by the Man Booker International and Nielsen in 2016 showed that translated fiction comprises 3.5 per cent of the UK literary fiction market, and of this low percentage, less than one-third of the books were by female authors – pushing them even further to the periphery of appreciation. Even though this is not the case for translators (statistics show that the majority of European translators are female), we need only look at the Dutch Europese Literatuurprijs, awarded annually to a European novel and its Dutch translation, to understand that initiatives promoting women in translation are not fighting an imaginary battle: the award’s 2016 longlist featured more naked women on book covers than there were female nominees

The Warwick Prize for Women in Translation was established in 2017 to address this gender imbalance and “to increase the number of international women’s voices accessible by a British and Irish readership”. Another opportunity for women to get their work translated is Women in Translation month, which takes place every August. During this month bookshops and publishers alike focus on the promotion of translated literature by female authors. Another example is the Women in Translation book club at the Lighthouse Bookshop in Edinburgh, which organisers Annie Rutherford and Mairi C Oliver discuss in the second episode of our Think in Translation podcast. Initiatives such as these not only encourage readership of translated books, but also give well-deserved acknowledgement to the underappreciated voices that bring valuable works into other languages through translation.

While literary prizes like those mentioned above help us to acknowledge diversity, a common criticism is that the proliferation of literary prizes has had a somewhat inflationary effect on their own value; an amusing example is the Times Literary Supplement’s satirical All Must Have Prizes Prize, which “honours” literary awards for ensuring that “no book is published without being longlisted for a prize”.

But literary awards face more structural issues than their overflowing number. The top three awards in the UK – the Man Booker prize, the Costa book of the year, and the Baileys prize for women’s fiction – all charge shortlisted publishers £5000, not including additional fees to represent selected works at events. With no guarantee that these costs will be outweighed by the increase in book sales, a lot of smaller publishing houses simply cannot afford to enter an author into the competition – meaning that any possible incentive these prizes give to small, risk-averse publishers may be eclipsed by the significant expense of even just being shortlisted. This may be doubly true for publishers of niche stories that are less likely to appeal to more mainstream audiences (though we acknowledge that readers of translated literature are potentially more likely to have tastes that depart from the mainstream).

The positive impact literary awards can make on readership is further impaired by the difficult balance they have to maintain between innovation and popularity. While awards offer the perfect opportunity to showcase literary trailblazers, dependency on sponsors and commercial interests can compel juries to select less experimental works, and ultimately this tendency affects the entries made by publishers. Thus literary awards are caught in the same web of commerce they originally tried to escape. This same propensity may manifest itself in awards focusing on literary translation; their selections are likely to promote only those foreign works that are regarded to be within the comfort zone of English-speaking audiences. In this way, as discussed here as well as in episode two of our podcast, awards that aim at broadening the horizons of Anglo-American readers risk excluding the works that are best set for this task. The line between originality and marketability is a fine one indeed, and it takes a delicate and skilful jury to get it right.

Just as the dominance of Anglo-American culture can tarnish the cultural landscape in other societies, its monopoly is equally harmful at home. No culture is self-sufficient, but with the profusion of cultural material from the USA and the UK, it has become difficult for outsiders to seduce Anglo-American audiences with foreign cultural products. This phenomenon is not limited to literary arts: music, television and cinema suffer from the same Anglo-centrism, which can ultimately lead to a kind of cultural ignorance. Some promising developments can be observed in certain cultural niches: the popularity of Scandinavian crime fiction has skyrocketed, and Japanese culture has found its way to a mainstream audience through manga and anime. Still, ask a random Brit or American about their favourite foreign author, and you are likely to be greeted by resounding silence.

When the English language offers an abundance of original material, confining yourself to the comforts of a known language and culture is an easy temptation to succumb to; coming into contact with foreign cultures helps you move beyond the borders of your reality. In a world of filter bubbles and polarised political landscapes, reading translations and stories told by unfamiliar voices is one way in which we can help bolster inclusivity and ensure that we are not closing ourselves off from Europe and the rest of the world. It is therefore important that continuous efforts are made to keep literary translation alive and growing.

While literary awards and book festivals may succeed in getting the attention of authors and publishers for translated literature despite the financial risks of the genre, it is not enough. True change in the literary market will only come about when both publishers and Anglo-American audiences develop their own interest in foreign cultural products; there will be no supply without demand, and vice versa.

References and Recommended Reading

"Women in Translation: Thoughts of a Female Translator", by María Gracia (Wolfestone, 8 March 2018)

"Lost to Translation: How English Readers Miss out on Foreign Female Writers", by Sian Cain (Guardian, 31 August 2017)

"All Must Have Prizes", by Michael Caines (Times Literary Supplement, 30 January 2017)

"On Eve of Costa Awards, Experts Warn that Top Books Prizes Are Harming Fiction", by Danuta Kean (Guardian, 2 January 2017)

"First Research on the Sales of Translated Fiction in the UK Shows Growth and Comparative Strength of International Fiction" (Man Booker Prize website 2016)

"Han Kang, Author of Booker Winner The Vegetarian, Whets Koreans’ Appetite for Literature" (South China Morning Post, 29 May 2016)

"The Change to the Man Booker International Prize Is Good News for Translated Fiction", by Daniel Hahn (Guardian, 8 July 2015)

Publishing Translated Literature in the United Kingdom and Ireland 1990 - 2012, by Alexandra Büchler and Giulia Trentacosti (May 2015)

About Anna Bruins: Anna Bruins is one of our interns working on the Think In Translation project. She was born and raised in the Netherlands, where she – after an interval in Seoul for her studies – graduated from Tilburg University with a Liberal Arts & Sciences degree in 2017. She is currently doing a postgraduate degree in Religion, Literature and Culture at the University of Glasgow. Her love of language was partially instilled into her by her education in a variety of languages, although her current fascination for non-Latin scripts is mostly due to her grapheme-colour synaesthesia. She has an existential fear of cracking joints and the colour spring green.

About Megan Lavery: Megan Lavery was born and raised in Glasgow and graduated in 2017 with an MA in French from the University of Glasgow. She currently lives in Edinburgh as she completes her MSc in Publishing from Edinburgh Napier University.

About Think in Translation: It's only natural that different languages produce different cultures: the words we use affect the way we think and the way we live. That's why reading books in translation opens your mind. We created Think in Translation to encourage people to read books in translation by making them more accessible – to remind readers that translated literature is available to everyone, and not reserved for specialised audiences. Through podcast episodes and blog posts we're exploring translation from various angles. Use #ThinkInTranslation on social media to join in the conversation.