Cynicism and Naivety

Cynicism and Naivety

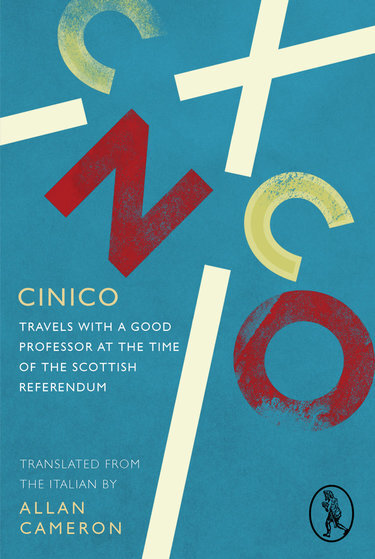

In this newsletter, I intend to promote my own novel, Cinico. Travels with a Good Professor at the Time of the Scottish Referendum, which was published in 2017. Like A Happy Little Island, I would like to sell through the more expensive edition so that we can release the cheaper one (this means selling the smarter and more expensive edition at a lower price than the new cheaper edition – does that sound like something Milo Minderbinder might have said in Catch 22?). I cannot judge my own work, so I will limit

myself to the genesis of this political satire.

My starting point was the 2014 independence referendum and Voltaire’s Candide, which for some reason seemed to be a good vehicle for this kind of story. I wanted the book to be as much about Europe as it was about Scotland, and I realised that a little time had to pass before I could really get going on it, because I needed to look at the referendum from a more historical viewpoint (two years at least). In my first few pages, I started with a French journalist called Candide! But very soon I realised that this was not going to work for two very good reasons: I didn’t know enough about France and the French, and the naivety of Candide did not suit the modern world or the profession he had decided to follow in that world.

For me, an Italian protagonist made much more sense, and the dominant mindset of our own times is cynicism (thought that may be changing). So Cinico was born as a cynical and slightly narcissistic Italian journalist living in London.

Cinico is quite similar in tone and structure to my second novel, The Berlusconi Bonus (Luath Press, 2005), which was translated into Italian and was quite successful in terms of sales and reviews (at a time when there were more book reviews in newspapers), although the subject matter was very different. So, the book more or less wrote itself over a period of two and a half months, broken up between other activities – mainly publishing.

It had to be funny, and I’m told by some that it is. I should add that The New Internationalist thought The Berlusconi Bonus “very funny” but The New Humanist decided that “It is never funny.” Humour, it seems, is in the mouth of the laugher.

As Cinico travels around Scotland he obviously meets lots of Scots, but he also meets a good cross-section of Europeans. The people he meets are not stereotypes of their nations, but individuals that add something to the debate from their own histories and viewpoints. The Ukrainian, for instance, is quite unlike some other Ukrainians I have met, and in this case the conversation was almost verbatim of something that happened to me – the inspiration came from an individual and not a country I’ve never visited. Of course, the full spectrum of ideas can be found in any nation, though the proportions supporting each idea can vary greatly. I use conversations, sometimes ones that occurred decades ago (often forty or more years ago, given that the exciting part of my life was in my teens and my twenties – after that it became sedentary and bookish). One of my short stories, “The Redistribution of Wealth” (Can the Gods Cry?, 2011), was copied from life and concerned characters who came to the tavola calda where I worked as its sole employee for twelve hours a day. The title refers to the genial method for setting prices, which I adopted from my Algerian friend who passed the job on to me when he returned to his own country.

Although I think that autobiographical fiction is very difficult to do and mostly inadvisable, this kind of writing was more observational than autobiographical, and practically everything in it really happened. Sometimes life cannot be bettered in terms of literary content.

This methodology was employed in Cinico, and immigration – a dominant theme in the book – arose from the lived reality of working in Italy before the UK joined the EU, which meant that I was illegal and could only be paid in cash. This also meant that I had no security and no health insurance. The communist doctor who worked in the lumpenproletarian district of Florence where I lived didn’t charge me, except once when he apologised profusely for charging me 500 lira (around 20p) which even then was a derisory figure (the same district has now been thoroughly gentrified). For a period, I lived with Algerian illegal immigrants like myself and that gave me a good understanding of the problems. Some of Chapter IX concerns events based on my friendship with a couple (he was Lebanese and she was Malaysian, but for reasons I can’t remember I changed them to an Algerian and a North Korean). They are a study in the overpowering isolation that illegal immigrants can suffer in such highly exploitative situations. For this reason, it is one of the chapters I am most proud of, though there are no laughs here. Just the sad brutality of how many people live in our midst.

Another unfunny episode is the “dying man” chapter, which has perhaps some philosophical merit. In 2018, a Russian novelist I know sent me an e-mail saying, “The Dying Man chapter is a thrill, I could not help writing to you immediately. I liked [how] the love affair turn[s] from rejection to acceptance, and the story about the ‘inventive’ father.” I value his judgement more than my own. Besides a published novel is like an old friend whose company you now find dull. There’s a residual fondness, but a tendency to forget about its existence for long periods of time. The dying man came entirely out of my imagination, as did Cinico and Maryanne, his lover and nemesis.

My experience of writing fiction is that central and more complex characters have to come out of the writer’s imagination.

This may sound counterintuitive, but we don’t really know the people we know. We either like or dislike their company, but that is a completely different matter, and they have control over what they give away of themselves.

Cinico is a Bildungsroman about a middle-aged man, and the change in the narrator is not damascene, but instead rather mundane, as he reflects on the failed referendum after having belatedly switched to the side of independence: “It came to me not as a bolt of lightning that enlightens and sharpens our focus on life, but as a mist billowing irregularly and inescapably in from the sea, obscuring and confusing as it goes. It changed me, but changed me slowly. The hope it brought was the feeble, bitter-tasting hope of resignation. The hope of someone who has at last learnt to live with their hopelessness. The knowledge it brought was the knowledge of my own ignorance, and with it, the marvellous sense of my own insignificance – and, what’s more, the insignificance of each moment in my life compared to my life as a whole: a Russian doll of insignificances.”

Some comments on Cinico:

" Allan Cameron’s modern Candide, an Italian journalist, whirls back and forth across the dark landscape of Scotland’s 2014 independence referendum like a shoogly meteor. Sometimes his cynical, witty comments light up the dark corners of Yes thinking, sometimes the sullen assumptions of the Better Together campaign. He meets and hears a score of fascinating characters with their own opinions, most of them foreigners making their own effort to understand the country. Towards the end, the fictional Italian writes down some of the wisest and most moving comments to be found on the epiphany of those amazing months [before the Independence Referendum].” – Neal Ascherson

“… there are deep insights and thoughts worth holding on to. … I enjoyed it much more the second time I read it and was better able to linger over the many nuggets that glowed for me. For, despite the occasional irritation with Cinico’s cowardice and specious self-analysis, I soon recognised that he has a human core which is open to change.” – Alex J. Craig, iScot

Allan Cameron, Glasgow, July 2020